Roberts:

“Courcelette is one of the shining names in the story of Canadian valour. The storming of that heap of ruins, which had once been a sunny Picardian village, nestling within its orchards, was an achievement forever memorable in Canadian history. In the final analysis it will show as a great operation perfectly planned, and executed with courage, swiftfulness and thoroughness. The glory of it belongs to the 2nd Division, which was highly trained and well seasoned to war by a year of strenuous duty in the tormented salient at St. Eloi.”

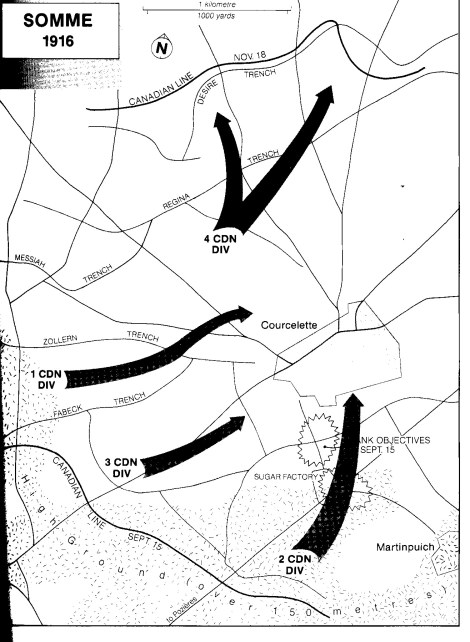

Although the assault was to be on a fairly wide front, including Canadian, British and French troops, we will concentrate on the 21st Battalion in the 4th Brigade of the 2nd Canadian Division (bottom right on the map below). It had the 20th and 18th Battalions on its right. The 19th Battalion furnished the “mopping up parties” and the 24th Battalion (temporarily attached to the 4th Brigade), was in reserve. It should be noted that, in the few days they had been in the Somme before the major offensive began, the Canadians had already suffered 2,600 casualties. So this attack on September 15 would be an escalation of the ongoing action.

An Australian named John Raws described the battlefield in the Somme and how he felt about life in the trenches:

“There are not even tree trunks left – not a leaf or a twig. All is buried and churned up again and buried again. If we live tonight we have to go through tomorrow night – and next week – and next month.”

Unfortunately he didn’t make it to the next month, being killed by a shell a few days later.

Report by Brigadier-General Rennie:

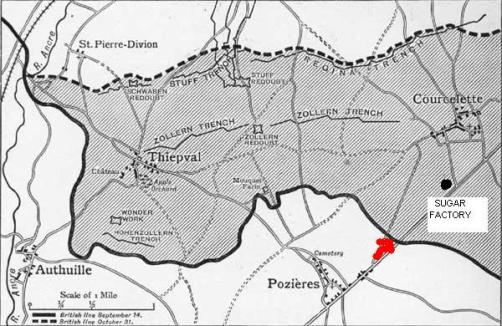

“Our task was that portion of the main objective between Martinpuich and Courcelette straddling the Albert – Bapaume Road, including the Sugar Factory and the well-garrisoned second-line German trench just beyond it. German prisoners taken recently told us the Sugar Factory was a strong position and should be expected to be defended with determination. Our artillery kept up a steady and very effective fire for three days and nights. This fire covered all enemy trenches within our zone of attack. The 21st Battalion was situated immediately to the left of the road leading out of Pozieres and directly in line with the Sugar Factory (See red arrow below).”

Roberts:

“The terrain over which the attack was to be made is of a gently undulating expanse of farm lands stripped naked by the incessant storm of shell fire and closely pitted with shell holes and craters. Of grass or herbage not a blade remained, of trees but here and there a bald and riven stump. Dividing this unspeakable waste runs the straight highway from Albert to Bapaume, thick strung with ruined or obliterated villages.”

In order to get there the 21st would likely have followed the same general route as the 20th.

Corrigall:

“The first units to move forward were the Scouts and Bombers, the former to tape out communications trenches, the ‘jumping-off line’ and the battalion flanks, the latter to establish advanced dumps of bombs and ammunition. Beyond La Boisselle, we passed some of our artillery set up in the chalk pit, formed from an earlier mine explosion. We moved down Sausage Valley to Brigade Headquarters, where we were issued bombs, flares and sandbags. At 2 AM we advanced again, entering Walker Avenue, the communication trench that was to lead us to the front line. Very soon we came under heavy, accurate artillery fire. The advance was slow, the trench became congested and we suffered many casualties. The experience was nerve-wracking. We had to push forward, over and past the dead and wounded, with shells bursting among us.”

George Hatch, of an unknown unit, tells of that same night:

“We were told there would be white tape along the wall of the trench to follow. We came to a place where the tape divided, and we didn’t know whether to go right or left. But we took the right and ended up where there’s no trenches. As we crawled over shell holes, we got within 35-40 feet of Germans and they were firing to beat the band. We were lost. A bullet hit the officer in charge under the nose and came out the back of his head. Dead as a doornail. I undid all my heavy equipment and crawled from shell hole to shell hole to get back where I came from, and the rest did too. We came to barbed wire, and we shouted to the boys not to fire. We got back in the trench. I don’t how many was killed, but it was an awful lot. That was our very first experience.”

Roberts:

“The artillery fire, which had started at 1 PM on the day before, ceased abruptly at 4 AM and there followed a sudden menacing calm, followed by the slow hours of waiting, always a stern test to the nerve of the most seasoned troops.”

21st War Diary:

“September 15 – The battalion was in position at 4:30 AM.” (I can’t believe how horrible it would be to sit in the dark for more than two hours with no sleep, under enemy fire, knowing that you would have to leap out of a trench and charge into machine gun fire or hand-to-hand combat. This was no longer about the cold, mud, rats, lice etc., the men were now dealing with pure terror or utter resignation). Brigadier Rennie said they were there at that time “to get a good rest before the 6:20 AM zero hour.”

Early in the morning the 4th Brigade defeated an attempt to rush our posts established in front of the line captured on the September 9. Pozieres was bombarded with German gas shells. The Trench Mortar Battery crew was split in two, with half going with the first wave and the other half to follow up with the reserves, after the initial target was captured and consolidated.

Corrigall:

“It was not a simple affair to form up the battalion for the attack. Each wave had to be extended across the frontage, the leading wave fifty to one hundred yards forward of the front line and the second and third waves in the front line and just in the rear of it. The moonlight was helpful but dangerous, in that movement could be so easily observed by the enemy.”

Roberts:

“At dawn the air was dry, crisp and clear – the bite of autumn in it. Patches of pale sky glimmered abundantly between driven fleeces of cloud. The ground gave firm footing.”

McBride:

“The rum ration is issued just before zero hour and is taking effect by the time the word comes along to be up and away. It serves to make men alert, mentally and physically, and their chances of reaching the first encounter with the enemy are much greater than if they are tired, benumbed with cold and apathetic. After that they uncover new and unsuspected sources of energy that will take them through the rest of the day.”

Corrigall:

“As far as the eye could see before us, the country consisted of low ridges and gentle valleys. The straight Bapaume road, with a row of shattered trees on either side, stretched to the horizon. In foreground were the enemy trenches. About three-quarters of a mile ahead stood the ruins of the Sugar Factory. Two villages, separated by about a half mile, and a mile and a quarter away, were on our immediate front, Martinpuich on the right and Courcelette on the left. After daybreak, things were fairly quiet, with no unusual aeroplane activity and ‘normal’ artillery fire. We ourselves were feeling anything but normal; in fact the spell of waiting was getting on our nerves. At last the storm broke. The roar was deafening.”

The new Creeping Barrage was a very effective tool because gunners were now better trained and their guns and ammunition were more reliable. The artillery (See British guns at the Somme, below) fired at targets for a fixed, predetermined period of time and then ‘crept’ their fire closer towards the enemy, giving the infantry a chance to follow quickly behind to subdue any survivors. Another innovation for this battle was that every unit was given a series of limited objectives, rather than trying to complete the assault in one concerted push. The reporting of objectives attained would give headquarters the ability to send up reserves where necessary and make it easier to decide when to attack the next set of objectives, while attempting to keep the entire front moving forward together. The barrage started at 6:20 AM.  The men (below) are Canadian soldiers in a reserve trench being shelled as the action begins.

The men (below) are Canadian soldiers in a reserve trench being shelled as the action begins.

Roberts:

“Here at the Somme front our battalions realized they would have the support of an overmastering weight of artillery. It was a tonic for them, after their long grueling time in the Salient at Ypres, where they had felt themselves ground down in the Flanders mire by bombardments from three sides at once and ceaselessly overlooked by an adversary holding superior positions. Here they felt they would have a chance ‘to get a bit of their own back’.”

Corrigall:

“The roar was deafening. The whirring shells whizzed over our heads and shrapnel spouted into the enemy’s trenches. From the German lines, flares –the SOS alarm – were shot frantically in the air. At 6:24 AM, with bayonets gleaming, we left the trenches. To right and left of us men were advancing at a walk in five waves, at intervals of about ten yards.”

Hatch:

“A whistle started to blow, daylight was breaking and the first tanks that ever roamed over no-man’s-land came across the trenches. I saw a wounded man scream like a horse. I saw blood coming out of their ears, out of their mouth. If you don’t think you get scared when that happens, you’re scared to death. We went over the top and advanced 1,100 yards to what had been a sugar refinery.”

Leslie Payne:

“I raised my head and looked at the Hun trench, and to my astonishment saw Heiny after Heiny up on the firing step, blazing wildly into us, to all appearances unmolested. Halfway across, the first wave seemed to melt away and we were in front…scared beyond measure. We, almost as one man, dropped into shell holes. Further progress and it is more than likely we would have stepped into a volley of grenades. Looking back not a man was moving…the situation seemed critical.”

At this point the sudden appearance of an Allied tank demoralized the Germans in this area and they left their trenches and ran.

A letter from Maheux:

“I am sending you a picture of the tanks. I fought in September beside some of them, but they got blew by shells or stuck in shell holes. They are like an alephan they are so big.”

The picture (left) shows a group of Canadian soldiers “inspecting” a tank at Courcelette. I suppose it could even be the picture Maheux sent to his wife.

The picture (left) shows a group of Canadian soldiers “inspecting” a tank at Courcelette. I suppose it could even be the picture Maheux sent to his wife.

McBride:

“I well remember the day tanks made their initial bow to the world in general and the Germans in particular. Sept 15, 1916 these monsters took to the field. They must have caused as much consternation in the enemy ranks as the gas did to ours when first used. They were great, ugly, ungainly things. I believe there were six of them in this area that day, and on the whole they acquitted themselves nobly. They waddled and snorted across the field, trampling down machine gun emplacements and generally making themselves useful. They would straddle a trench and then enfilade the occupants with machine gun fire or deposit a bomb or two where they would do the most good. Then the enemy artillery found some and put them out of commission. I remember one, half capsized alongside the road, with name ‘Crème de Menthe’ on its side.”

This was the first use of tanks and the results were not really very encouraging. Many of them failed to start and several quickly became bogged down. Their best speed was a half-mile per hour, they were vulnerable to artillery fire and liaison with the infantry was very poor. On the other hand, the sight of these 28-ton monsters seemed to have a devastating effect on German morale. Sir Douglas Haig saw enough potential in these new machines of war to request that 1,000 more be built.

Roberts:

“Just prior to the assault, a party of 6 snipers was posted in the shallow jumping-off trench to keep busy an enemy detachment of about twenty men, which had been troubling our lines. All except Private Stevens were killed or wounded, and Stevens had two holes in his steel helmet, a deep wound in his left shoulder, and a gash in his forehead. He kept on sniping and killed several of the enemy. His rifle was smashed by a shell just as the assault went forward. He picked up a rifle with fixed bayonet and, moving forward with the assault, entered an enemy strong point. He single-handedly captured five Boche and brought them back to our line.”

On that first day, a 21st Battalion soldier named James Halliday (right) of Port Hope moved forward. An exploding shell killed two comrades beside him and wounded him. He made his way to an old German trench, where he could not be reached for two days. He was found dead on September 16. Meanwhile the battle moved ahead.

On that first day, a 21st Battalion soldier named James Halliday (right) of Port Hope moved forward. An exploding shell killed two comrades beside him and wounded him. He made his way to an old German trench, where he could not be reached for two days. He was found dead on September 16. Meanwhile the battle moved ahead.

Corrigall:

“Once in the German front line, we found that our artillery fire had been very effective. Many dead and wounded lay about; most of the remainder surrendered, those showing fight being quickly disposed of.”

Roberts:

“The progress of the wave is so strictly scheduled that it often leaves behind small enemy posts or dugouts sheltering furtive bands of machine guns in its rear. Behind the waves come the mopping-up parties, whose job it is to ferret out the hidden posts, clear the dugouts, and gather in the prisoners. The advance of the 4th Brigade (and the 21st Battalion) on all its fronts was so rapid and irresistible that it left behind plenty of work for its mopping-up parties.”

Lieutenant-Colonel Jones – 21st Battalion:

“On our advancing, some of the enemy offered to surrender but in most cases these men were bayoneted by our advancing troops. Near the Bapaume Road about thirty of the enemy left the trench to retire. These men were all accounted for by our rifle fire.”

McBride:

“War automatically declares an open season on men. You shoot or stab or club them and think no more of it than you do of breaking a clay pigeon. There’s nothing very personal about it but you know that if you don’t get the other fellow, he will probably get you – and you do your best.”

Corrigall:

“The whole enemy front line was in our hands by 6:35 AM. A minute later, leaving the “moppers-up” to deal with the prisoners we were off again, following after the artillery barrage. We came across an intermediate trench, captured it and carried on, reaching the final objective shortly after 7 o’clock. Our airplanes came over sounding their klaxon horns. We flashed our pocket mirrors in the sunlight to show them our position.”

Roberts:

“Within fifteen minutes of going over, the brigade was in possession of another line of German trenches from three to four hundred yards behind the first line. A party of the enemy threw up their hands and surrendered to a company of the 18th Battalion. As the captain was accepting their surrender, one of the party threw a bomb at him and blew him to pieces. The captain’s followers flung themselves forward in a fury, and not one German in that sector of the trench escaped the steel.”

21st Brigade War Diary:

“At the second trench, the battalion suffered greatly by reason of machine gun fire, which came from our left flank. At this time, all officers of “B” Company and several other officers were casualties.”

Roberts

“The three assaulting Battalions of the Brigade succeeded in maintaining an even front. The 18th and 20th reached their final objective – The Candy Trench — just after 7 o’clock, preceded by three or four minutes by the 21st who had reached the Sugar Factory and taken a position there. The Factory had already been knocked about by our guns and was now surrounded by our troops on three sides. After a mad half-hour of hand-to-hand struggle in a hell of grenade and machine gun fire, from the dreadful turmoil of grunting, cursing and shouting, the blood and the sweat of savage bodily combat, victory suddenly emerged. The heap of ruins was in our hands, along with 125 prisoners of whom ten were officers. One of the companies, which distinguished themselves in this Homeric bout – “B” Company of the 21st Battalion- was commanded and most efficiently handled throughout the crisis by Sergeant-Major Dearer. Every one of its officers had fallen during its hard-fought advance along the Bapaume Road.

The unexpected swift collapse of the Sugar Factory was hastened by one of the tanks. Its path was spread with panic, in the teeth of the most concentrated fire. It waddled deliberately up to the barriers of the Sugar Factory, trod them down without haste or effort and exterminated a machine gun with its crew. Then it made a slow circuit of the factory to blot out a troublesome nest of machine gunners and to preside over the submission of horror-stricken Huns.”

21st Battalion War Diary:

“At the Sugar Factory we did not receive as much opposition as we expected. About 125 of the enemy surrendered. We also took six officers and fifteen men as prisoners out of a deep dugout under the factory. They first refused to surrender, but on our using “P”(smoke) bombs, they were glad to do so. Approximate strength of our frontline was 200 all ranks and four machine guns.

“D” Company, who were to dig the halfway trench, commenced work at 7:20 AM and consolidated the position. All officers were casualties and the company strength is down to fifty Other Ranks, one Lewis gun and one Colt Gun.” (By noon they were down to thirty-seven Other Ranks)

The picture at right shows what the newspaper called “an armored car” at the Somme. It appears to be some sort of wagon, which could be pushed or towed into position

The picture at right shows what the newspaper called “an armored car” at the Somme. It appears to be some sort of wagon, which could be pushed or towed into position

Message from 21st Battalion:

“8:10 AM. – Casualties estimated at 30 in “C” Company, due to men being too eager and traveling too fast.”

I wonder if this meant they met the enemy before they expected to or, in their haste, they were caught in their own creeping barrage.

Corrigall:

“Looking back, the battlefield presented a strange spectacle. Most conspicuous were the abandoned tanks. The “moppers-up” were using prisoners as auxiliary stretcher-carriers. Wounded were staggering back, the more serious cases being aided by others better able to walk. Runners were coming forward or going back with messages. Signalers were running out lines, and the gallant stretcher-bearers, carrying their first aid haversacks were rushing from one casualty to another, indifferent to incessant artillery fire.”

Message from 21st Battalion:

“8:30 AM. – Lieutenant Miller reports front line in good shape. We have lost our Lewis guns and we need 50 more shovels.”

On either side of the 4th Brigade the battle was progressing well also. When the 28th Battalion captured a particularly troublesome machine gun emplacement they found a German gunner who had been chained to his gun. There were steel stakes driven into the ground on either side of him. He was attached to them with one chain around his waist and another locked to an iron ring on his leg.

Message from 21st Battalion:

“50% of officers are casualties. Please send reinforcements of one company for evacuation of wounded and work.”

In a daring reconnaissance by Captain Heron and a patrol from the 20th Battalion, it was discovered that Gun Pit Trench, which was about 500 yards further forward was lightly held. In the process, they killed some Germans and returned with two captured machine guns and two prisoners.

Roberts:

“The 4th Brigade, promptly grasping the unexpected opportunity, swept forward in a new – and thoroughly impromptu – attack. Before 10 o’clock, the trench was in our hands, with fifty prisoners, another machine gun and three trench mortars. Still unwearied, the Battalions pushed on and gained a line along the eastern side of the Sunken Road, where, by one o’clock, they had dug themselves in. This handsome and unpremeditated gain greatly simplified the consolidating of our position at Candy Trench and the Sugar Factory, and immediately made practicable the main operation against Courcelette itself.”

21st Battalion War Diary:

“Total strength of those reaching the frontline at the Sunken Road was three officers and about 100 Other Ranks.”

Message from 21st Battalion:

“Noon – We have four Lewis guns. The engineers are constructing a strong point in the Sugar Factory. One Stokes gun is in front line (Bill and/or Keith?). Sniping is active, presumably from Courcelette.”

Corrigall:

“About noon the enemy had located our new position and began to shell our line and the supports in Candy Trench. At 2:30 PM his infantry attempted a counter-attack, which was repulsed by machine gun and Lewis gun fire.”

The picture shows German soldiers at the Somme moving through shell holes towards someone’s barbed wire.

Roberts:

“At 3:30 PM the order came for the 5th Brigade to pass through and take Courcelette that day.”

2nd Division comment:

“5:25 PM – Prisoners’ opinion of tanks say that it was not war, but butchery.”

4th Brigade memo to 19th and 21st Battalions:

“5:45 PM -Your battalion will be withdrawn tonight. You may commence to evacuate your wounded as soon as the 5th Brigade passes through.”

Corrigall:

“At 6 PM we watched them (the 5th Brigade) coming down the slope from Pozieres, shells bursting among them, but on they came steadily, passed through us and on to assault Courcelette, which they were successful in capturing.”

McBride:

“A battalion that goes in on the second wave has quite likely been shelled from the time it reaches the area, far back along the transport lines. It has probably reached this point only after forced marches. It begins its tedious progress toward the point from which it is to continue the advance. In the strongly entrenched areas, this route lies over a trackless waste, much worse than open country. There are no roads, few recognizable landmarks. The communication trenches have been shelled to pieces, or are filled with the wounded coming back. The front melts away at one place, is pushed back by a counter-attack in another, while at a third it has encountered a stubborn redoubt, and at a fourth suddenly pushed forward, leaving an ominous gap, which might mean disaster. With daylight they are more able to guess at their bearings and might learn a little from questioning wounded or stretcher-bearers or signalers. They cannot, of course be called fresh troops. They are tired, chilled and sluggish; their boots are heavy with mud and their eyes with lack of sleep. They may face troops who are well fed and rested. They may have little artillery support or none at all. Once in the fight they will take care of themselves, but the first few minutes may reduce their strength by as much as twenty percent.”

Roberts:

“Before 7:30 PM the whole of Courcelette, with some 1,300 prisoners was in our hands and the position was being consolidated. All through the night and for several days after, the Germans strove, by furious shelling and desperate counter-attacks, to regain the stronghold. But all the enemy efforts resulted only in further loss of ground and further punishment.”

4th Brigade:

“7:40 PM – The villages of Martinpuich and Courcelette are now in our hands.”

Message from 21st Battalion:

“Midnight – Present strength in front line is about one hundred and ten Other Ranks. In halfway trench, twenty-five Other Ranks. I have suffered heavily by enemy shelling since 3 o’clock. I have no reserve on hand and my runners are gone.”

21st Battalion War Diary:

“September 16, 1 AM – Lieutenant McGee (who would die that same day) brought sixty Other Ranks to the Sugar Factory.”

Corrigall:

“When the comparative quiet of the night settled down over the battlefield, our minds were filled with a strange mix of rejoicing and sadness. We joked about missing ‘blighties’ and in fighting Huns. We shouted with glee at stories of the discomfiture of panic-stricken prisoners. Then someone spoke of the loss of a comrade, of how he fell, and of the loss to the section. During the night the clear brilliance of the moon enabled us, in spite of the activity of hostile artillery fire, to work on consolidation and to carry up stores and rations.”

Hatch:

“When daylight broke the next morning, I remember a group of Canadian boys, still in their new uniforms. They were reinforcements. They were digging to change the trench around and a shell came in. As I stood on top of the trench the shrapnel pellets were going all around me feet. At least twenty-five of the boys that just got to the trenches were killed right there and then. The dirt from that explosion knocked me flat on my face. I put my hand on the back of my neck, and off came skin and hair and everything.”

Corrigall:

“The weather continued fine and we managed to get some rest, although the enemy shelled us very heavily around noon. Later on they attempted two counter-attacks against the 21st Battalion on our left. Our machine guns and Lewis guns literally mowed down the advancing wave. Both attacks failed.”

Message from 21st Battalion (Who have not yet withdrawn):

“3:20 PM – Have started consolidation – no picks, just shovels. Men are very tired but doing best possible. Occupying ground in Sunken Road. Frontage about 125 yards. Total number of men – 75. Shelling has been going on for two hours.”

Report by two sergeants of the 21st Battalion:

“The battalion was occupying the Sunken Road. It was about 6 PM when a party of about 150 prisoners was behind our front line carrying some of our wounded on stretchers and bearing a large Red Cross flag in front of the party. The Huns turned their artillery on them and started a bombing attack on our left flank. Things looked awkward for us as the enemy were coming at us from the front and, with the Sunken Road full of prisoners behind us, it would have been quite easy for them to have combined their efforts and cleaned up on the lot of us. We soon found out that our prisoners were only too anxious to remain prisoners and our rifle and machine gun fire proved too hot for the bombing party and they never reached our lines.”

4th Brigade Orders include the following note:

“4th Brigade Machine Guns and 4th Brigade Trench Mortar Battery will withdraw with the infantry. Owing to severe casualties in these units, the infantry will assist with carrying parties, should they be called upon to do so.”

“4th Brigade Machine Guns and 4th Brigade Trench Mortar Battery will withdraw with the infantry. Owing to severe casualties in these units, the infantry will assist with carrying parties, should they be called upon to do so.”

Message to Brigade:

“8 PM – Officer commanding 21st Battalion reports his battalion has no officers and less than 100 men. Could the relief be expedited to safeguard this flank?”

Hatch:

“When night time came, I was told to follow a communication trench and it would take me to the medical unit. It was very dark and shells were exploding overhead. I was standing in something and every step I took I went down to my hips. It was a communication trench full of Australian dead bodies. They had been there for a month or so, and the smell was something. I got 100 yards through that trench and came to another. There I found two boys, squatted down facing one another to escape the artillery fire. Even though I shook them they would not say a word. I found a dugout, but I couldn’t see down into it. I stepped down five or six feet and felt some cloth. Because I was scared I lay down there to escape the shrapnel and I fell asleep. When daylight broke the next morning I found I was lying between two dead Germans.”

Claire Tisdall (below) who served at the Somme Casualty Clearing Station:

“I was up for seventeen nights before I had a night in bed. A lot of the boys had legs blown off or hastily amputated at the front line. These boys were the ones in the worst pain and I often had to hold the stump in the ambulance for the whole journey so it wouldn’t bump on the stretcher.”

Message from King George to the 4th Brigade received 9:30 PM:

“I congratulate you and your brave troops on the brilliant success just achieved. I have never doubted that complete victory will ultimately crown our efforts and the splendid result of the fighting yesterday confirmed this view.”

4th Brigade to Major Elmitt, 21st Battalion:

“September 17, 4:29 AM – Please organize and take forward to Battalion Headquarters a party of fifty men who will carry with them, in addition to 24-hour’s rations, sufficient rations and water to supply the remainder of the battalion now (still) in the lines.”

Order to 4th Brigade Trench Mortar Battery:

“September 17, 12:10 PM – Please hand over to 5th Brigade four stokes guns with crews.”

Sergeant Blackburn:

21st Battalion Bombers – “We were relieved at 4:30 AM on the 17th after holding the line at the Refinery for about twenty-four hours and the Sunken Road about twenty-four hours without food and water.”

The 21st was relieved and arrived at the Sunken Road Valley at 6:10 AM, where they were given a hot meal and allowed to rest until 3 PM. Then they started back to the Brickfields, arriving there at 7 PM. Muster parade was held on September 18 and twenty Officers and 385 Other Ranks were found to be casualties.

McBride:

“What did this battle cost? I have some figures for the 21st Battalion. There were six officers and seventy-four men killed. As to the wounded I have no figures, but they usually run about four or five to every man killed, so it can readily be understood that it was a real battle. Other battalions, I am told, suffered even more serious losses.”

Desmond Morton:

“In its most glorious and costly day of the war, the 21st Battalion took the German-held ruins of the Sugar Factory at Courcelette and lost all but sixty-four of its men.”

Corrigall:

“The next day it rained heavily. During the morning the impressive muster parade was held, where the quartermaster called the roll. An absentee might be killed, wounded or missing. Nothing hurt so deeply as hearing the name of a comrade called – once, twice, three times, when we knew that perhaps no answer could possibly be given. Our casualties were: three officers and 75 Other Ranks killed and seven officers and 204 Other Ranks wounded.”

Desmond Morton:

“Maheux emerged from the Somme campaign as a Sergeant, with one of the sixteen Military Medals the 21st Battalion earned for its role at Courcelette.” He wrote this to his wife (slightly edited) – “I past the worse fighting there since the war started. We took all kinds of prisoners but God we lost heavy, all my camarades killed or wounded, we are only a few left but all same we gain what we were after. We are in rest dear wife. It is worse than hell the ground all covered for miles with dead corpses and your Frank past all true without a scratch. Pray for me dear wife I need it very bad. I went true all the fights the same as if I was making logs. I baynetted some killed others. I was caught in one place with a chum of mine he was killed beside me. When I saw he was killed I saw red. We were the same like in a butchery, the Germans when they saw they were beaten they put up their hands but dear wife it was too late. If a poor soldier killed here doesn’t go to heaven without stopping no place, I believe there is none. I was allway in the worst place that the way I got my stripes and my medal but I suppose my time was not up. Now I never work at anything just giving orders. I am here the same as the foreman in the chanty but more men to look after. Instead of cutting trees we are doing our best to killed as much as possible.”

Once again Bill Nesbitt and Keith Roblin were among the unwounded survivors.

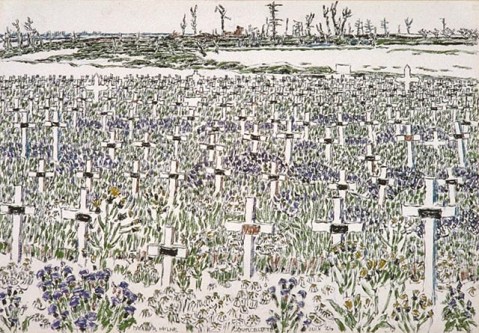

This is what noted Canadian artist David Milne recorded about Courcelette.

I wish I had asked Keith and Bill what their roles were in this battle. In Keith’s case his official records provide few details; he might have been returned to the Trench Mortar Battery on September 11th, he might have joined an infantry company of the 21st Battalion or he might have been held out of the battle (at least for the first little while). The latter does not seem to fit since he was promoted from Corporal to Sergeant on the first day of the battle. This would indicate to me that he earned a battlefield promotion to replace another Sergeant, who had been killed or wounded. As for Bill, it seems that the Trench Mortar Battery was very much in the thick of things and he seems to have been fortunate not to have made the casualty list.

I am not sure why, but the 21st Battalion, along with the 4th Brigade and the rest of the 2nd Division, including Bill (and perhaps Keith) in the Trench Mortar Battery, set out on what seems to me was a 6-day trek around France. The first day, September 17, they went about eight miles to Vadencourt in the pouring rain. The picture (below) shows Canadian troops on the march.

54th Battalion History:

“Vadencourt was an apology for a hamlet, lying on the hill above Contay where the Canadian Corps Headquarters had been established. It remains a damp and dismal memory of rain-soaked shelters erected in a dripping wood on soggy soil.”

The day after that they marched 16 miles to La Vicogne for two nights and one day of generally cleaning up. On September 21, they moved in fine weather to Berteaucourt and good billets. Again they stayed for two nights and the War Diary says – “About a hundred men were able to get a bath at St. Leger.” That would be more than a week since their last bath and not all of them were even able to get that.

On September 21, 1916 Sergeant-Major Bill Nesbitt was assigned to the 39th Reserve Battalion at West Sandling, England. On the recommendation of his Commanding Officer, Captain Morrison, who felt he would make a good Trench Mortar Officer, he was sent to obtain his commission. He would return to the battlefield three months later in December 1916.