Armageddon:

“The rain kept bucketing down. Years of shelling had destroyed any natural drainage system. Roads, trees, buildings, all had been demolished, leaving a sea of mud marked chiefly by occasional ruins, derelict tanks and guns, and bottomless lakes over mine and shell craters. By the end of August, the British had lost 68,000 men to regain St. Julien and part of Pilckem Ridge.”

On September 20, when the wet weather moderated somewhat and while the 4th CMR were still at Arras, the British and Australian forces, having already sustained 120,000 casualties, began another offensive and made some progress into early October. On the 3rd, Sir Douglas Haig told General Currie that his Canadian forces were needed to take the ridge at Passchendaele. Currie protested. Like other Canadians, he knew the Ypres salient and hated it and warned that he would lose sixteen thousand men. The Germans occupied higher and somewhat drier land and their artillery was able to reach every part of the salient. But Haig said:

“Passchendaele must be taken”.

Corrigall:

“General Currie told us (the 22nd Battalion) that he had begged the commander-in–Chief to spare the Canadians the ordeal of Passchendaele but his plea had been refused because the pressure on the enemy had to be maintained. He pictured, wisely without minimizing them, the nature and trying conditions of operations in the salient. Everyone became distinctly less happy.”

Armageddon:

“Then, on October 4, the rains returned; driving, drenching torrents that restored the churned soil to an endless sea of stinking mud, spotted with bodies of horses, men, and all the detritus of war. Wounded men drowned in it. When eight or a dozen stretcher-bearers were needed to move a single casualty, too few reached hospitals. For the first time, Germans found British soldiers eager to surrender and talking of killing their officers.”

4th CMR History:

“On October 15, the battalion marched to Savy to go by train through Hazebrouke to Caestre, where they marched (five miles) to the Koorten Loop area, on the border of Belgium. They trained there for five days in a picturesque valley of farms, and had ideal weather.”

Lieutenant Grey of the 20th Battalion describes parts of the same journey a week later:

“At Ligny I was detailed to command the station guard, and after posting a sentry in each box-car, allotted compartments to the officers. The journey was uninteresting. At the halts, which were frequent, it was part of my duty to see that the men stayed on the train – as easy as keeping water out of a leaky boat. On arrival at 5:30 PM it was dark and wet. None were dry when the battalion reached Caestre, but all were tired and slept that night soundly in spite of wet clothes.”

4th CMR History:

“On October 21, they marched back to Caestre and boarded a train to the ruined city of Ypres (left). Many of the men had never been in Flanders; for them it was a thrilling experience to be amidst the wreckage of the town, the very name of which was synonymous with all that was terrifying.”

“On October 21, they marched back to Caestre and boarded a train to the ruined city of Ypres (left). Many of the men had never been in Flanders; for them it was a thrilling experience to be amidst the wreckage of the town, the very name of which was synonymous with all that was terrifying.”

The Canadian Engineers grappled with the difficult task of providing safe transport for both men and artillery. Enormous resources were applied to rebuilding roads and gun platforms, carving drainage ditches and laying duckboard tracks. The duckboards were essential because slipping into the mud could mean drowning, particularly for wounded soldiers who did not have the strength to pull themselves free. All this activity had to be carried out under continuous artillery fire from higher ground, strafing from fighter planes and bombing from the German Gothas both day and night. This air activity far exceeded what had been experienced before.

The duckboards were essential because slipping into the mud could mean drowning, particularly for wounded soldiers who did not have the strength to pull themselves free. All this activity had to be carried out under continuous artillery fire from higher ground, strafing from fighter planes and bombing from the German Gothas both day and night. This air activity far exceeded what had been experienced before.

4th CMR History:

“This new form of terrorism was bombing. Organized aerial raids at night became a most demoralizing factor, darkness no longer bringing consolation. Every night, and especially on moonlight nights, the drone of enemy planes could be heard as they crossed overhead. Their great height gave the feeling that they were hovering directly above, searching out and preying on the individual. It was hard to remove the delusion that one was being singled out by an invisible demon in the sky. Few things were more trying to the morale.”

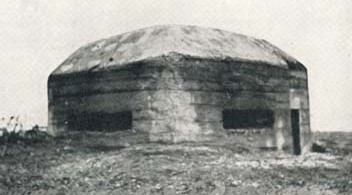

One advantage of the mud was that the shells and bombs buried themselves underground and did much less damage than if the ground had been dry. Nevertheless the engineering troops suffered almost 1500 casualties before the fighting had even begun. The Third Canadian Division and the 4th CMR would enter a battle already in progress. The Germans had had considerable time to fortify the area with concrete “Pillboxes” with walls five feet thick, which housed men and machine guns. They were under strict orders from Field Marshall von Hindenburg not to give up any territory and, if they did, were to counter-attack immediately. Currie’s plan for his sector was to move forward in small increments, to give the artillery time to catch up. The weather had been dry for a week but on October 20 the rains came again.

4th CMR History:

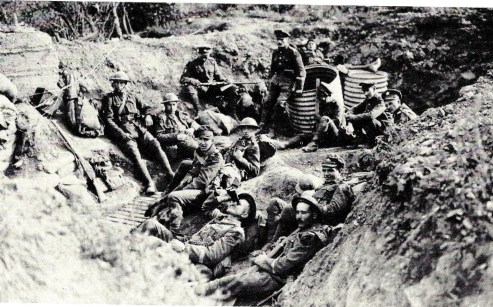

“Again they were tossed into the maelstrom of a huge offensive. They became part of the great whirlpool of traffic. The roads leading to and from Ypres were jammed with all kinds of vehicles, from bicycles to gigantic caterpillar-drawn howitzers. The steady stream of men and animals never ceased; field kitchens, limbers, G. S. Waggons, and pack ponies nose-to-tail made an endless chain. Troops from every corner of the globe passed and repassed; labour-corps worked unnoticed in the cosmopolitan medley of fighting and non-combat troops. When they arrived in their allotted area, the majority made themselves as comfortable as possible in an open field (Perhaps like the 22nd Battalion below). As soon as darkness the enemy aircraft were in the sky.”

Arthur-Joseph Lapointe, of the 22nd Battalion told what he saw:

“Before us, some two kilometres away, stretched the ridge of Passchendaele. At the foot of this ridge lay a low plain, pockmarked with countless shell holes filled with stagnant water. Everywhere was an air of desolation. Not a house was to be seen as far as the horizon. Only the bare, terribly scarred plain, over which a cataclysm seemed to have passed. It was as if life could never return to these killing fields.

In a flooded trench, corpses of Germans, their stomachs grotesquely bloated, floated in slushy water. Here and there were bodies buried in the mud with only an arm or leg showing above the surface. Macabre faces appeared, blackened by their long stay on the ground. Everywhere I looked, all I could see was corpses covered in a shroud of mud.”

And this was even before the Canadians went into battle. The next day the 4th CMR relieved, in the Reserve Area California Trench, New Zealand troops, who had sustained many casualties and were anxious to leave as soon as possible.

4th CMR History:

“The next day the battalion moved into support. Two very popular and valuable officers were in the support line that night when their dugout received a direct hit and they were both killed. On October 24 they relieved the 1st CMR in the front line. This was one of the worst reliefs the battalion ever experienced. Carried out at night in a heavy rain, it was almost impossible to make any headway through the sticky mud; the guides lost their way in the trackless swamp and it was 5 AM before the relief was completed. When daylight came they saw that on their right was Wolf Copse and Bellevue Spur, a strongly held position about five hundred yards up the slope leading to Passchendaele, which was twenty feet higher and approximately twenty-five hundred yards away.

In the darkness of the early morning of October 26, the companies assembled in their theoretical positions. They carried out these difficult maneuvers without interference from the enemy. Heavy clouds threatened rain, it was difficult to see, there were few landmarks and, as the officers and men had been in the line only one day, they had very little opportunity to orient themselves and to determine their objectives. To illustrate the difficulties of maintaining a sense of location, the guides who brought in the battalion got lost on several occasions. As soon as the bath-mat track was left all was hopeless.

In the darkness of the early morning of October 26, the companies assembled in their theoretical positions. They carried out these difficult maneuvers without interference from the enemy. Heavy clouds threatened rain, it was difficult to see, there were few landmarks and, as the officers and men had been in the line only one day, they had very little opportunity to orient themselves and to determine their objectives. To illustrate the difficulties of maintaining a sense of location, the guides who brought in the battalion got lost on several occasions. As soon as the bath-mat track was left all was hopeless.

Lieutenant Bill Nesbitt, who left Battalion Headquarters about midnight to join his company, which he was leading into action at 5:40 AM, got lost, although he had less than 1,000 yards to go. Twice he found himself behind the enemy’s lines and on both occasions was challenged by a German but managed to escape; finally, after floundering around in the mud all night almost exhausted he located his company just before zero hour.

When the battalion started to assemble, each man was in fighting kit with two hundred and twenty rounds of ammunition. Unfortunately, drinking water, which was badly needed, never reached the front line and the men went into action with empty water bottles.

“D” Company was on the rAt zero hour, one hundred and eighty 18-pounders, sixty 4.5 Howitzers and about one hundred and twenty-five Heavies of various description opened up on the Divisional front. Trench mortars (right) concentrated on the barbed wire, which was not very formidable and on the pillboxes, which were almost immune. A gentle rain began to fall and the first of the assaulting troops went forward in a drizzle in the hazy dawn. In the confusion of battle, it was impossible to retain a definite formation and, as in other attacks, such regularity soon collapsed; the troops pushing forward as best they could. “C” Company under Lieutenant Nesbitt was on the left, with “B” Company seventy yards behind. ight with “A” Company behind. Machine gunners followed and, in fifteen minutes, the second wave started.

“D” Company was on the rAt zero hour, one hundred and eighty 18-pounders, sixty 4.5 Howitzers and about one hundred and twenty-five Heavies of various description opened up on the Divisional front. Trench mortars (right) concentrated on the barbed wire, which was not very formidable and on the pillboxes, which were almost immune. A gentle rain began to fall and the first of the assaulting troops went forward in a drizzle in the hazy dawn. In the confusion of battle, it was impossible to retain a definite formation and, as in other attacks, such regularity soon collapsed; the troops pushing forward as best they could. “C” Company under Lieutenant Nesbitt was on the left, with “B” Company seventy yards behind. ight with “A” Company behind. Machine gunners followed and, in fifteen minutes, the second wave started.

The enemy retaliated with a heavy barrage and machine gun fire, inflicting heavy casualties. The men moved slowly across the slime, around the brimming craters, over and through entanglements until they were forced to take cover in freshly made shell holes. In two hours they progressed only 500 yards. The task was entirely different from that of Vimy where the artillery had obliterated all opposition. Here the enemy had to be fought step by step across the open.”

The enemy retaliated with a heavy barrage and machine gun fire, inflicting heavy casualties. The men moved slowly across the slime, around the brimming craters, over and through entanglements until they were forced to take cover in freshly made shell holes. In two hours they progressed only 500 yards. The task was entirely different from that of Vimy where the artillery had obliterated all opposition. Here the enemy had to be fought step by step across the open.”

The 4th CMR History goes into some detail about the German reinforced concrete pillboxes (below). However, at Passchendaele they were not constructed with openings for firing as shown here but were primarily for shelter; taking the place of a deep dugout. During a bombardment soldiers stayed inside to be protected from the artillery fire but, when under attack, the soldiers came out to trenches beside or behind the pillbox. Then they were just as vulnerable to mortar, rifle and grenade fire as they would have been in a conventional trench.

By 10 AM, the battalion had outstripped the battalions on its flanks and especially on its right where the 43rd Battalion was being driven off its perilous perch on Bellevue Spur. Two officers of the 52nd Battalion, with two companies that had been in reserve, attacked the spur and successfully captured it. The 4th CMR “A” Company on the right only had a few survivors; one officer had been killed and two wounded. The same conditions applied to “D” Company. Nevertheless they succeeded in digging a trench and consolidating the line by 2:30 PM.

A soldier of the 18th Battalion said:

“Most of us carried on because of, not limitless, but more than ordinary issues of rum.”

4th CMR History:

“On the left the conditions were similar. “C” Company struggled against a most grueling opposition; pushing forward until the effectiveness of the force was reduced by casualties. All the officers were hit; two were killed and Lieutenant Nesbitt, the Company Commander, and another officer were wounded. Major Hart passed on with his “B” Company, gathering in the remnants of “C”. Assisted by platoons from the 1st CMR, he too was able to dig in and consolidate by 2:30 PM.

During the attack Lieutenant Nesbitt had a miraculous escape; seeing a German about to shoot at him, he dived forward for the protection of a shell hole. His flight was in the same plane as the trajectory of the bullet which ploughed a furrow (through his left ear and shoulder and) down his back parallel to his spine without killing him.”

McBride:

“In close fighting, the difference between life and death is measured in terms of hundreds of a second. That’s all. There is no second chance. Either you get him or you don’t. If you are on your toes, your eyes open, your whole self on the job, you get him.”

Advancing troops were not allowed to stop and care for wounded soldiers. All men carried an emergency field dressing and, if possible, attempted to treat their own wounds. The wounded soldier then had to wait until the stretcher-bearer arrived. He would be taken to the Regimental Aid Post (likely in a reserve trench) where the Medical Officer cleaned the wounds, applied dressings and gave injections.

A British stretcher-bearer, who later became a Member of Parliament:

“The whole place was a sea of mud, and the scene still remains incoherent in my memory, falling into shell holes, losing our way, wet and tired, we felt all the time rather impotent. But the work was done. All the wounded, including some who had lain out there for forty-eight hours, were brought in and most of the dead buried. Some died before we could get stretchers to take them back to the dressing station.”

Bill’s condition was described on his medical files as “dangerously wounded”. No doubt he would have been taken to a Forward Aid Post (See a picture of one at Passchendaele above). Then he was transported and admitted to the No. 4 Casualty Clearing Station (below ) before being sent three days later to the No. 2 Red Cross Hospital at Rouen.

Ida Downs, describing No. 4 CCS:

“This was frequently the scene of the most distressing sight which human eye can witness; the rewounding and killing of already wounded men by an enemy bomb dropped suddenly in the night. There was hardly a moonlit night that the Hun did not visit our area and drop bombs. I was impressed with the bravery and fortitude of the women nurses. Night bombing is a terrifying thing. I believe the nurses showed less fear than anyone. Nurse Helen Fairchild represented the truest type of womanhood and stood for the very best in the profession.”

American Helen Fairchild, (right) writing from No. 4 CCS:

“Dear Mother, I am with a operating team close to the fighting lines. We all live in tents and wade through mud to and from the operating room, where we stand in mud higher than our ankles. I’ll sure have a lot to tell when I get home.”

“Dear Mother, I am with a operating team close to the fighting lines. We all live in tents and wade through mud to and from the operating room, where we stand in mud higher than our ankles. I’ll sure have a lot to tell when I get home.”

Nurse Fairchild died a few months later from “a massive stomach ulcer, possibly made worse by exposure to enemy gasses.”

Chief Nurse Julia Stimson wrote about CCS’s:

“What with the steam, the ether and the filthy clothes of the men, the odor in the operating room was so terrible that it was all any of them could do to keep from being sick. (Their job was) no mere handling of instruments but sewing and tying up and putting in drains, while the doctor takes the next piece of shell out of another place. Then, after fourteen hours of this with freezing feet, to a meal of bread and jam. Off to rest if you can in a wet tent in a damp bed without sheets, after a wash with a cupful of water.”

Bill’s Medical Report:

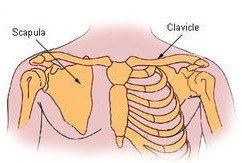

“September 30, 1917 – The Superior medial angle of the left scapula is missing. Evidently there was complete sloughing of the trapexius muscles from its border down along the vertebral border of the scapula involving all the muscles down to the ribs. The left scapula is practically fixed to the thorax by this scar. Movement of the left shoulder girdle is practically nil. The shoulder joint is normal. Any movement involving motion of left shoulder girdle causes pain in the scar.”

4th CMR History:

“The battalion paid heavily for its part in the first stage in the capture of Passchendaele; an enormous sacrifice for such little ground gained. There were seventeen casualties among the officers; eight were killed and nine wounded. There were only four untouched who were part of the attacking troops and some of them had most uncanny escapes. Three hundred and four Other Ranks were killed, wounded or missing, or evacuated suffering from exposure. The few hours of fighting accounted for half the strength of officers and a third of all the men. The battalion gave more than its share of manpower. It left and never returned to Ypres or Passchendaele. Two of their greatest sacrifices had been made on this soil. Passchendaele was a rebuke for Sanctuary Wood. They left a battalion’s strength in the soil of Belgium.”

The battle continued until November 6 when Haig ordered a stop to the offensive. The Canadians had incurred 15,654 casualties – only a few short of Currie’s estimate of 16,000 and there were in excess of 300,000 Allied casualties. Six months later the Germans would retake Passchendaele.

Sergeant Maheux of the 21st Battalion:

“I past threw the battle of Passchendaele without a scratch. It was one of the worst place I was in – there’s no name for it.”

Winston Churchill:

“This adventure was a pathetic and unprecedented waste of bravery and human life”.

But perhaps writer Siegfried Sassoon summed it up best:

“I died in hell –

(They called it Passchendaele); my wound was slight

And I was hobbling back, and then a shell

Burst slick upon the duck-board; so I fell

Into the bottomless mud, and lost the light.”