by John Stephens

Their names were Genia Rickerson and Nonna Hopper. To a casual observer, they led a normal life in their latter years on a small apple farm, HOPRICK, on RR#4, Brighton. This land, in 2025, is now occupied by numerous recently-built homes and Legacy’s Brighton Retirement Residence.

To understand more about these women, we must go to Imperial Russia in the year 1900. Russia was a vast empire with a diverse population of around 128 million people. The Russian economy was largely agricultural, employing two-thirds of the population and producing about half of the national income. The country was controlled by a Tsar (at this time, Nicholas the Second, above), and had an upper class comprising royalty, clergy, and nobility, which accounted for approximately 14% of the population.

Nevertheless, that consisted of 1,900,000 people. (Princes And Princesses would form a small percentage of that number). There was also a tiny middle and working class. The upper class, who owned all the land, was conservative, protective of their wealth, opposed to reform, and dependent on the Tsar. They dominated the positions of influence in the army and civil service.

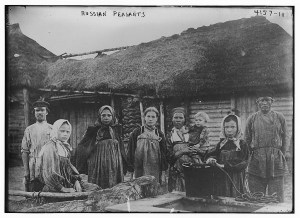

Over three-quarters of the Russian population were unhappy with their position in the Empire. Peasants and workers alike suffered horrendous living and working conditions, and hence posed a threat to the Tsarist regime.

Over three-quarters of the Russian population were unhappy with their position in the Empire. Peasants and workers alike suffered horrendous living and working conditions, and hence posed a threat to the Tsarist regime.  Discontent increased in the years before 1905 in the form of illegal strikes and protests. Russia had no form of income tax. The Tsar taxed the produce of the peasant farmers to raise money to maintain his regime. The burden of taxation was so great that periodic riots broke out.

Discontent increased in the years before 1905 in the form of illegal strikes and protests. Russia had no form of income tax. The Tsar taxed the produce of the peasant farmers to raise money to maintain his regime. The burden of taxation was so great that periodic riots broke out.

The Russian nobility consisted of Princes, Counts and Barons. The House of Tsereteli was a noble family in the Russian territory of Georgia as far back as 1395, when Constantine II conferred the title of Prince upon them.

In 1901, one branch of the family consisted of Colonel Peter Phyllimonovitch Tseretelli and his wife Sophie Victoria Goloubtzova. One family member described the Golubchof family, ”The name Golubchof was given to our ancestors for loyalty, courage and winning wars, back in the 14th century.” So the marriage of Peter and Sophie was a union of two aristocratic families. The Tseretellis lived on an estate in St. Petersburg, given to Sophie’s father by the Tsar. They had a second residence 30 or 40 miles away called Belye Strougi.

On May 9, 1901, they had a daughter, Princess Eugenia Tseretelli (Genia) and on March 12, 1903, another daughter, Princess Anna Tseretelli (Nonna). Noble families in St. Petersburg lived a life of luxury and privilege in magnificent townhouses with servants and governesses for their children. They had plenty of leisure time and enjoyed frequent social gatherings, picnics and trips to the seashore.

However, Russian expansion towards Asia was resented by Japan, which attacked Russia in February 1904. The war lasted until September 1905, when a Russian fleet was destroyed by Japan. Colonel Tseretelli led a regiment but was shell-shocked so that he was no longer able to live with his family. The clouds of discontent continued to form over Russia, and people began to lose respect for the tsarist regime and the Tsar himself. This culminated in a march to the Winter Palace (below) to plead for reform.

However, Russian expansion towards Asia was resented by Japan, which attacked Russia in February 1904. The war lasted until September 1905, when a Russian fleet was destroyed by Japan. Colonel Tseretelli led a regiment but was shell-shocked so that he was no longer able to live with his family. The clouds of discontent continued to form over Russia, and people began to lose respect for the tsarist regime and the Tsar himself. This culminated in a march to the Winter Palace (below) to plead for reform.

Although the Tsar was not in the palace, scores of steelworkers were gunned down and killed. This triggered a wave of general strikes, peasant unrest, assassinations and political mobilization that became known as the 1905 Revolution. Industrial workers laboured under appalling conditions. The average working day was 10.5 hours, six days a week, but 15-hour days were not unknown. There were no annual holidays, sick leave or pensions. Workplace hygiene and safety were poor; illness, accidents and injuries were commonplace, and with no leave or compensation available, sick or injured workers were summarily dismissed. The day after the killings, around 150,000 people in the capital showed their disgust by refusing to work.

Soon the strikes expanded around St Petersburg and other cities in the empire, including Moscow, Odessa, Warsaw and the Baltic states. Later, these actions became more coordinated and were accompanied by demands for political reform. Over the course of 1905, Tsarism faced its most dire challenge in its three-century history. Constant protesting and striking caused the Tsar to declare the October Manifesto. In it, he agreed to a new constitution and pledged a nationally elected parliament, which was called the Duma (below right).

The Duma was the lower house of parliament, with the State Council of Imperial Russia as the upper house. It was made up of landowners, merchants, city intellectuals, peasants, and representatives of the industrial middle class. However, the Duma could not pass legislation without at least a 50% vote from the State Council, and the Tsar retained a veto. Despite some changes in membership, the Duma proved to be mostly ineffectual and was dissolved in 1917.

The Duma was the lower house of parliament, with the State Council of Imperial Russia as the upper house. It was made up of landowners, merchants, city intellectuals, peasants, and representatives of the industrial middle class. However, the Duma could not pass legislation without at least a 50% vote from the State Council, and the Tsar retained a veto. Despite some changes in membership, the Duma proved to be mostly ineffectual and was dissolved in 1917.

The main events of the 1917 Revolution took place in and near Petrograd (now once again Saint Petersburg), the then capital of Russia, where long-standing discontent with the monarchy erupted into mass protests against food rationing on March 8. Revolutionary activity lasted about eight days, involving mass demonstrations and violent armed clashes with police. On March 12, the forces of the capital’s garrison sided with the revolutionaries. Three days later, Nicholas II abdicated, ending the Romanov dynastic rule. On March 22, the former Tsar was reunited with his family at the Alexander Palace at Tsarskoye Selo. He and his family and loyal retainers were placed under protective custody in the palace by the Provisional Government.

The main events of the 1917 Revolution took place in and near Petrograd (now once again Saint Petersburg), the then capital of Russia, where long-standing discontent with the monarchy erupted into mass protests against food rationing on March 8. Revolutionary activity lasted about eight days, involving mass demonstrations and violent armed clashes with police. On March 12, the forces of the capital’s garrison sided with the revolutionaries. Three days later, Nicholas II abdicated, ending the Romanov dynastic rule. On March 22, the former Tsar was reunited with his family at the Alexander Palace at Tsarskoye Selo. He and his family and loyal retainers were placed under protective custody in the palace by the Provisional Government.

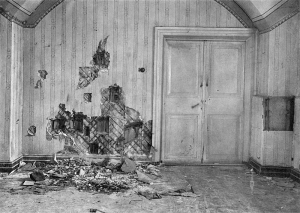

In the latter part of 1917 and in the spring and early summer of 1918, the Tsar and his family were subjected to increasing restrictions, the loss of many servants and several moves to much inferior accommodations.  Although it has never been uncovered who issued the order, an assassination was carried out on July 17, 1918, of the Tsar, his wife, his five children and five members of the royal entourage in the basement of the house (above right) where they were being held. Their bodies were mutilated, burned and buried to avoid identification.

Although it has never been uncovered who issued the order, an assassination was carried out on July 17, 1918, of the Tsar, his wife, his five children and five members of the royal entourage in the basement of the house (above right) where they were being held. Their bodies were mutilated, burned and buried to avoid identification.

The Tseretelli girls would have been shielded from the events between 1905 and 1917 as they lived with their mother and were tutored with the usual education of the nobility, which we know from later information included the French, English ,German and Russian languages – taught in that order. French was the language spoken at the dining table. One person told me that Nonna had said that they often played with the children of the Tsar at the royal palace. This would seem plausible because the Tsar’s three younger children were born in 1899, 1901 and 1904 making them contemporaries of Genia (1901 and Nonna (1903). Nonna said “We spent lots of time at Belye Strougi, all the Christmases, summers. Guests would come and we had wonderful lives there. Lots of piano concerts. The servants would get up about 3 o’clock and start our breakfast. Childhood memories are of tenderness, of warmth and of mother who would always come and bless us”.

However, their comfortable lifestyle would come crashing down (likely around 1917, when they were 16 and 14) when they and their mother were arrested and imprisoned. Under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin (left), private ownership of land was abolished. In later years, when I knew them, they were reluctant to talk about their experiences, but a few things seemed to have escaped the veil of silence. The prison also housed vermin. They were released before their mother. Their foreign language skills may have played a part in their release. When they got out, they were assisted by former servants and an English couple to find a place to live. In light of subsequent information, I assume that they moved at some time to Tchiatouri, Georgia, a place known to the Tseretelli family as far back as 1879, when a Tseretelli ancestor discovered manganese deposits there.

However, their comfortable lifestyle would come crashing down (likely around 1917, when they were 16 and 14) when they and their mother were arrested and imprisoned. Under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin (left), private ownership of land was abolished. In later years, when I knew them, they were reluctant to talk about their experiences, but a few things seemed to have escaped the veil of silence. The prison also housed vermin. They were released before their mother. Their foreign language skills may have played a part in their release. When they got out, they were assisted by former servants and an English couple to find a place to live. In light of subsequent information, I assume that they moved at some time to Tchiatouri, Georgia, a place known to the Tseretelli family as far back as 1879, when a Tseretelli ancestor discovered manganese deposits there.

I have no idea when the sisters arrived in Tchiatouri, but they might have been there during the Rebellion of 1922. If not, they certainly would have heard about it afterwards. In that year, the Communists sent troops to occupy Georgia, and an era of domination and depression began, including prison, widespread killings and deportation to Siberia. Georgian resistance was met with force. One Georgian resistance group called for the execution of Russian occupiers and listed a number of killings in the area, including – “In the Tchiatouri industrial region, the number of people shot is not yet known. The rebel forces of this region, whom they could get hold of, were put in goods wagons, locked in, and then salvoes of machine guns were opened. These wagons with a human cargo of about 195 were used as targets. Most of the persons thus shot were manganese ore miners or railway workers.”

I have no idea when the sisters arrived in Tchiatouri, but they might have been there during the Rebellion of 1922. If not, they certainly would have heard about it afterwards. In that year, the Communists sent troops to occupy Georgia, and an era of domination and depression began, including prison, widespread killings and deportation to Siberia. Georgian resistance was met with force. One Georgian resistance group called for the execution of Russian occupiers and listed a number of killings in the area, including – “In the Tchiatouri industrial region, the number of people shot is not yet known. The rebel forces of this region, whom they could get hold of, were put in goods wagons, locked in, and then salvoes of machine guns were opened. These wagons with a human cargo of about 195 were used as targets. Most of the persons thus shot were manganese ore miners or railway workers.”

On 18 August 1924, the Damkom resistance group laid plans for a general insurrection for 2:00 am on 29 August. The plan of the simultaneous uprising miscarried, however, and, through some misunderstanding, the mining town of Chiatouri rose in rebellion a day earlier, on 28 August. This enabled the Soviet government to put all available forces in the region on alert in a timely manner. Yet, at first, the insurgents achieved considerable success and formed an interim government of Georgia chaired by Prince Giorgi Tsereteli. The uprising quickly spread to neighbouring areas, and a large portion of western Georgia and several districts in eastern Georgia were wrested out of Soviet control. The success of the uprising was short-lived, however. Although the insurrection went further than the Cheka (Soviet secret police) had anticipated, the reaction of the Soviet authorities was prompt.

Stalin dissipated any doubt in Moscow of the significance of the disorders in Georgia by the one word: “Kronstadt”, referring to the Kronstadt rebellion, a large-scale though unsuccessful mutiny by Soviet sailors in 1921. Additional Red Army troops under the overall command of Semyon Pugachev were promptly sent in, and Georgia’s coastline was blockaded to prevent a landing of Georgian émigré groups. Detachments of the Red Army and Cheka attacked the first insurgent towns in western Georgia—Chiatiuri, Senaki, and Abasha—as early as 29 August and managed to force the rebels into forests and mountains by 30 August.

Stalin dissipated any doubt in Moscow of the significance of the disorders in Georgia by the one word: “Kronstadt”, referring to the Kronstadt rebellion, a large-scale though unsuccessful mutiny by Soviet sailors in 1921. Additional Red Army troops under the overall command of Semyon Pugachev were promptly sent in, and Georgia’s coastline was blockaded to prevent a landing of Georgian émigré groups. Detachments of the Red Army and Cheka attacked the first insurgent towns in western Georgia—Chiatiuri, Senaki, and Abasha—as early as 29 August and managed to force the rebels into forests and mountains by 30 August.

The suppression of the rebellion was accompanied by a full-scale outbreak of the Red Terror, “unprecedented even in the most tragic moments of the revolution,” as the French author Boris Souvarine puts it. The scattered guerrilla resistance continued for several weeks, but by mid-September, most of the main rebel groups had been destroyed. Stalin himself is quoted to have vowed that “all of Georgia must be plowed under”.

In a series of raids, the Red Army and Cheka detachments killed thousands of civilians, exterminating entire families, including women and children. Mass executions took place in prisons, where people were killed without trial, including even those in prison at the time of the rebellion. The exact number of casualties and the victims of the purges remains unknown. Approximately 3,000 died in fighting. The number of those who were executed during the uprising or in its immediate aftermath amounted to 7,000–10,000 or even more. According to the most recent accounts, 12,578 people were put to death from 29 August to 5 September 1924. About 20,000 people were deported to Siberia and the Central Asian deserts. Soviet rule was now complete.

I know nothing more about Genia and Nonna’s lives until 1926 or 1928 when Ronald Hopper and Ira Rickerson came into their lives.

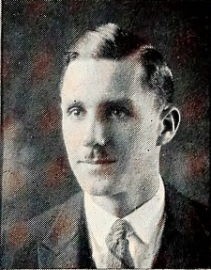

NONNA

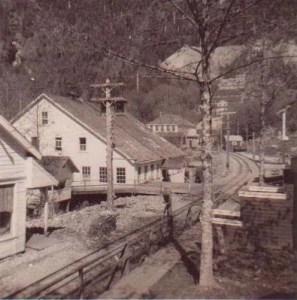

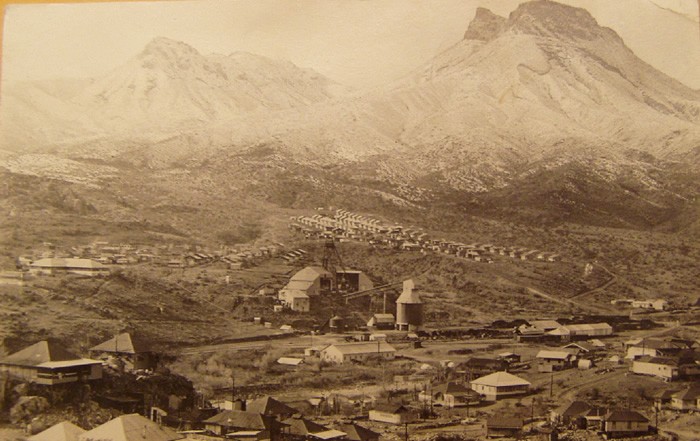

Ronald Hopper, a 25-year-old graduate engineer from McGill University, who was born in Vancouver, boarded the RMS Aquitania as one of 610 first-class passengers in New York in June 1926. On arrival in Southampton, England, on the 22nd, he declared that he was en route to Russia and intended to make his future residence in another part of the British Empire (likely Canada). Ronald’s destination in Russia must have been Tchiatouri (below) because he later wrote a master’s degree thesis: “The Manganese Deposits of Tchiatouri, Georgia, Russia”. Manganese is an essential element in all commercial-grade steel.

In a later declaration, Nonna stated that her mother was a resident of Tchiatouri, and Genia and Electrical Engineer Ira Rickerson were married in Tchiatouri in May 1928. So the Tsereteli family had lived in Tchiatouri, and the two engineers worked at a local mine.

The mines were high up on the hilltops and supplied a significant portion of the world’s supply.

Tchiatouri was the only Bolshevik stronghold in Menshevik Georgia. 3,700 miners worked 18 hours a day, sleeping in the mines, always covered in soot. They didn’t even have baths. Joseph Stalin, then 27 years old, persuaded them to back Bolshevism. They preferred his simple 15-minute speech to his rivals’ oratory. They called him “Sergeant Major Koba”. He set up a printing press, a protection racket and “red battle squads”. The mine owners actually sheltered him as he would protect them from thieves in return, and he destroyed mines whose owners refused to pay for protection. This would be the start of his eventual rise to power in Russia.

Since the mines were almost the only business in the town, I am assuming that Nonna worked there, perhaps providing French, English and German language services to the owners. A Brighton Independent article states, “Nonna and Ronald were married in Russia and again en route in Finland. After a tense encounter with authorities, they entered Finland, and Nonna persuaded Ronald that she needed her own passport. “I said to my husband ‘darling’ (she called everyone Dahling), I cannot be put as a little fly on your passport. I want to have my own passport. Let’s go to the British Ambassador and get my own passport. And that’s what we did.”

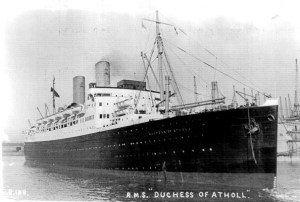

On July 13, 1928, the Hoppers sailed aboard the Duchess of Atholl on its maiden voyage from Liverpool, England, to Quebec City, en route to his parents’ home in Highland Park, Ottawa.

On July 13, 1928, the Hoppers sailed aboard the Duchess of Atholl on its maiden voyage from Liverpool, England, to Quebec City, en route to his parents’ home in Highland Park, Ottawa.

They arrived on July 26th. I cannot find a record of their wedding, which probably took place in Tchiatour,i but she stated that her mother was a current resident of Tchiatouri. Nonna was described on a pre-approval form to enter the United States as age 25, weight 135 lbs., with brown eyes.

Ronald returned to McGill University to obtain his Master of Science degree and produce his thesis on mining in Tchiatouri. Nonna took a business course there, but despite taking such a course, her daughter said Nonna never worked outside the home.  In the 1931 Canadian Census, they were boarding in Thetford Mines, Quebec and Ronald is described in the census as a Geologist working at the asbestos mine (right) and earning $3600 per year during the Great Depression.

In the 1931 Canadian Census, they were boarding in Thetford Mines, Quebec and Ronald is described in the census as a Geologist working at the asbestos mine (right) and earning $3600 per year during the Great Depression.

Next, Ronald began working in the gold mining industry, and his new assignment was in Michipicoten, an area near Wawa, Ontario. Nonna was confined to keeping house and walking the muddy streets, a couple of miles from their rental home to the mine, to take Ronald his lunch. In 1934, they were living and working in Timmins, Ontario, which had some of Canada’s most lucrative gold deposits. The town was developing its infrastructure, including road improvements. While roads were still not fully paved, cars were becoming more visible, and the town was developing a “motor-minded” culture.

Something that might have interested Nonna was The Russian Village Restaurant on Third Avenue, well-known for its turkey dinners (offered for 40 cents), home-made pastry and a large variety of sandwiches. Their daughter, Nona Elsie, was born there in August of that year.

Another new adventure was living in Belleterre, Quebec, which could only be reached by a small propeller bush plane, and the town was a sea of mud. In 1930, prospector William Logan discovered gold near Mud Lake. This led to the establishment of the Belleterre Gold Mines Company in 1935 and the formation of the Belleterre community at nearby Sables Lake to house the miners and their families. The community consisted of a few hundred (mostly French-speaking) people. A far cry from her former lifestyle in St. Petersburg. I believe it was here that Nona Elsie told me that they hosted future Quebec Premier Maurice Duplessis and his wife for dinner, and he brought Nonna a comb set.

Their next move was to Rouyn, Quebec, around 1937. The area had developed around mines with squatters moving in, with undisciplined municipal development featuring many muddy roads and no sidewalks and mines with a history of foreign workers and strikes. Around that time, cars were often known to backfire, and apparently, Nonna reacted with alarm, thinking the noise was gunfire. Nonna was paying a price for her freedom, but she managed the transition with grace and dignity.

Their next move was to Rouyn, Quebec, around 1937. The area had developed around mines with squatters moving in, with undisciplined municipal development featuring many muddy roads and no sidewalks and mines with a history of foreign workers and strikes. Around that time, cars were often known to backfire, and apparently, Nonna reacted with alarm, thinking the noise was gunfire. Nonna was paying a price for her freedom, but she managed the transition with grace and dignity.

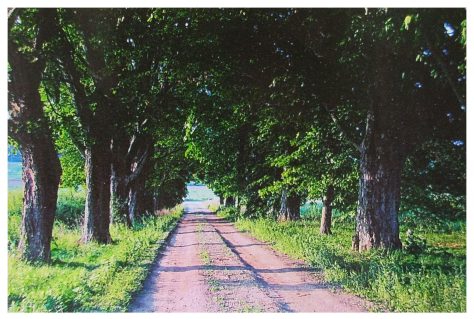

In 1939, they bought a farm with a beautiful 2-story house with large rooms and high ceilings in Brighton to serve as a home base when they weren’t working on location. I have been unable to locate a picture of the house, but an aerial photograph at right gives us some idea of the layout. Entry to the property is from Main Street (Hwy 2 – top right) down the long row of trees, a right turn to a loop around the house (Just below the current Braeburn Street) to the entrance on the south side. The rubble at the bottom center shows the outline of the demolished barn. The remainder of the farm stretched to the south over the railroad tracks and included an apple orchard and pasture land for cows.

I believe they were living at that time in the extremely remote community of Surf Inlet (left) in British Columbia. It was located on Princess Royal Island, a large, now uninhabited island on the North West Coast of British Columbia. It is located in an extremely remote area of British Columbia, 520 kilometres (320 mi) north of Vancouver and 200 kilometres (120 mi) south of Prince Rupert. Access during the mining years was via the coastal steamship companies. The mine was located on a mountainside several miles from the coast, following a chain of small lakes to the mine site. I think the site was about as remote as anywhere in Canada. Wildlife on the island included kermode bears, black bears, grizzly bears, deer, wolves and foxes, and nesting populations of golden eagles and bald eagles. However, for many years, it was the largest producer of gold in Canada until it shut down in 1942.

I believe they were living at that time in the extremely remote community of Surf Inlet (left) in British Columbia. It was located on Princess Royal Island, a large, now uninhabited island on the North West Coast of British Columbia. It is located in an extremely remote area of British Columbia, 520 kilometres (320 mi) north of Vancouver and 200 kilometres (120 mi) south of Prince Rupert. Access during the mining years was via the coastal steamship companies. The mine was located on a mountainside several miles from the coast, following a chain of small lakes to the mine site. I think the site was about as remote as anywhere in Canada. Wildlife on the island included kermode bears, black bears, grizzly bears, deer, wolves and foxes, and nesting populations of golden eagles and bald eagles. However, for many years, it was the largest producer of gold in Canada until it shut down in 1942.

Nona Elsie tells a story that occurred when she was around seven years old. She developed appendicitis and, as they approached Prince Rupert, they were stopped by the marine authorities and told that they would be unable to enter the harbour. There was concern that the Japanese might have mined the harbour. After explaining their situation, the family was allowed to enter at their own risk, which they did successfully. During this time, Nona Elsie spent some time in a Vancouver private school.

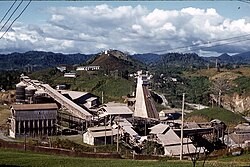

I don’t know when Nonna became a Canadian citizen, but there is evidence that it was some time before 1962. Nona Elsie. was married in August 1960. At that time, Ronald and Nonna were living and working in Siuna, Nicaragua, although I am not sure when they first moved there. The town of Siuna was the site of La Luz (gold) Mining company (above), which was active from 1936 to 1968. It was developed initially from an open pit and then underground for seven levels to a depth of 440 metres (1450’). The nearby Rosita Mine was developed in the early 1950s to mine copper, and they had ties to both mines. Nona Elsie recalls a dinner at their home with the President of Nicaragua and soldiers guarding the house. They were in Nicaragua until Ronald retired in 1966 and were shown in town data at the farm on Main Street, Brighton, in 1968.

GENIA

Ira D. Rickerson was born around 1886 in Minden, Louisiana and married Gwen Harvey (born in Essex, England in 1889) in 1907. The marriage took place in Cochise, Arizona, and Ira was living in Cananea, Mexico. Three years later, they were living in Yuma, Arizona, and he was described as an Electrical Engineer at a copper mine. They had at least one child, Arthur, who was born in 1913 in Arizona.

In 1918, Ira was the Electrical Engineer at the Ray Arizona Telephone Company. Ray (above) was a company town created in 1909 to house workers at the Arizona Hercules Copper Company. Today, it is a ghost town. The next reference to Ira that I can find is his arrival in New York on the Essequibo from the Pacific coast town of Balboa, Panama, on February 15, 1927. He is listed as single and lives in Shreveport, Louisiana. In this case, “single” must mean “divorced” because we have records of his wife, Gwen and son, Arthur, living in Los Angeles seven years later.

Fourteen months after he arrived in New York, Ira (age 42) married Genia (age 26) on May 5, 1928, in Tchiatouri, Russia. They wasted no time in getting out of Russia because they arrived three months later in New York on the S S Cleveland, an older German ship. Unlike her sister, who left Russia through Finland and England, Genia and Ira came through Hamburg, Germany and then by ship to New York. Additional data shows that she had $300 and she was “in transit” to the Sabinas Mining Co. in Juarez, Mexico, of which I can find no details. She said her mother was now back living in St. Petersburg. Genia was awarded Permanent Residency status in the United States on December 8, 1928, in Rouses Point, New York.

In April 1929, Genia gave birth to their first child, Leonard Randell, in Ventnor City, a suburb of Atlantic City, New Jersey, where they lived for a year. Then they spent some time in Brazil before sailing to New Orleans on August 19, 1930, aboard the Rio de Janeiro Maru (above) to their new home at 658 Topek Street, Shreveport, Louisiana. Genia was pregnant with her daughter, Alice Jea,n during the 19-day ocean trip and gave birth seven weeks after their arrival.

In April 1929, Genia gave birth to their first child, Leonard Randell, in Ventnor City, a suburb of Atlantic City, New Jersey, where they lived for a year. Then they spent some time in Brazil before sailing to New Orleans on August 19, 1930, aboard the Rio de Janeiro Maru (above) to their new home at 658 Topek Street, Shreveport, Louisiana. Genia was pregnant with her daughter, Alice Jea,n during the 19-day ocean trip and gave birth seven weeks after their arrival.

On December 11, 1931, Genia petitioned for U. S. citizenship under the name Eugene P. Rickerson while living at Coushatta Road, Shreveport and pledged her allegiance to the United States of America on March 12, 1932, signing her name Jean P Rickerson (to “americanize” her name ???). They also lived in Key West, Florida, in July 1940, when they applied to the Canadian Immigration Service to move to Canada with $575 cash and $500 in possessions between them. Their reasons for applying are as follows.-

“Ira, American-born, was raised on a farm, finished school and travelled through South America and Europe as an Electrical Engineer; met his wife in Russia. Returned to the U.S. and lived with his brother for a time; decided to settle on a farm in Canada. Has purchased a $10,000 farm in Brighton and has two small children.”

“Jean Tseretelli was born in St. Petersburg, Russia; met her present husband while he was employed in that country as an Electrical Engineer; became a naturalized U. S. citizen and induced her husband to settle down on a farm.”

THE BRIGHTON DAYS

Ron and Nonna were still working away from Brighton, and it was decided that Ira (known in Brighton as Rick) and Genia, with their children Leonard and Alice, would live and work on the farm until the Hoppers returned to the farm full-time. The population in the town of Brighton was 1,600. In a few years, teenager Leonard left home and, in later years, lived in the States.

Tragedy struck when an accidental fire burned the house to the ground along with most of their belongings. Genia and Alice spent some time with the neighbouring Raney family, and Rick lived on the farm in a small trailer to tend to the dozen or so cows, a horse and the apple orchard. In time, the house was rebuilt, but as a bungalow, and things returned to normal. This included taking the cows to pasture and back because the pasture was south of the railroad tracks and somehow they managed the farm with only a tractor and a horse and without a car. Rick died in January 1954 and was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery, Brighton. Genia took over the running of the farm.

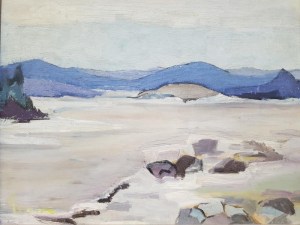

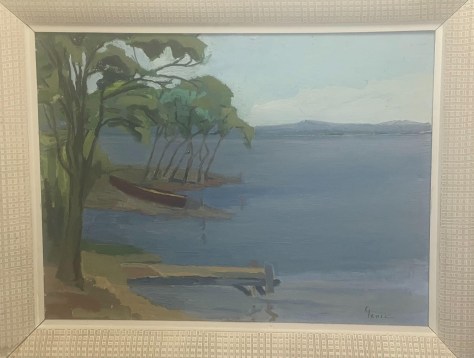

Around 1948, Genia took an interest in painting and took lessons from a Finnish-American artist, Paavo Airola, who lived north of Colborne. An article published in an American newspaper in Virginia in March 1960 shows that Genia entered 20 paintings in the Spring exhibit of the Virginia Beach Art Association. She described her work.

“ I like the impressionists best. There the object is an impression rather than a copy of nature. I like simple lines of softness – a certain amount of mysticism. I try to paint a few hours every day”. She said that she would paint anything but a portrait commission. “These people, they want to be beautiful. It is complicated to please both the public and yourself. I please myself and don’t paint portraits. I try to paint a few hours every day. If you like something very much, you’ll find the time.”

An article published in the Colborne Chronicle in March 1962 states: “Word has been received of Mrs. Genia Rickerson’s one-man showing of 39 oil paintings at Managua, Nicaragua. Mrs Rickerson, a talented and prominent Brighton artist, has been spending the winter at the Nicaraguan home of her brother-in-law and sister Mr and Mrs. Robert (sic) Hopper.”

Genia seemed reserved and often would be quietly serving or cleaning up at a party, even those that were not at her house. To me, she was an ordinary citizen of a small Canadian town with a slightly different accent. She certainly was very serious about her painting. She would likely have been proud to know that her artistic talent had been recognized after her passing in the Biographical Index of Artists in Canada by Evelyn McMann in 2003, and that some of her paintings were shown at the Robert McLaughlin Gallery in Oshawa in 2013 and later at the Art Gallery of Northumberland.

Genia seemed reserved and often would be quietly serving or cleaning up at a party, even those that were not at her house. To me, she was an ordinary citizen of a small Canadian town with a slightly different accent. She certainly was very serious about her painting. She would likely have been proud to know that her artistic talent had been recognized after her passing in the Biographical Index of Artists in Canada by Evelyn McMann in 2003, and that some of her paintings were shown at the Robert McLaughlin Gallery in Oshawa in 2013 and later at the Art Gallery of Northumberland.

One source described her artwork as “suggesting that Rickerson’s pieces contribute to a narrative of diverse styles and media reflecting strength and delicacy”. The painting below was given to my wife and me by the sisters as a wedding present.

Another side of Genia is revealed in an article in the “What’s Cooking” section of the Virginian-Pilot of Norfolk, Virginia, four months after her art exhibit, under the heading “Globetrotter’s Cuisine”. The article states that, “because she was born and lived in Russia and now resides in Canada, her cuisine is a rare combination of Russian and French Canadian”. It also mentioned that her art would be on display again at a local show. Her recipes were listed with an occasional comment.

- French Canadian Pork Pie – “The pie may be frozen if desired. It is easily reheated. Freezing was really a secret of the country people. They would put the pies in the snow and use them as needed during the Christmas holidays”.

- St. Laurent Pie – “Mrs. Rickerson makes sweetbread and mushroom pie by a recipe which came from Mme. Louis St. Laurent, wife of a former Prime Minister of Canada”.

- Creole Stuffed Eggs – From her days in Louisiana?

- Chicken Creole Ring – Also Louisiana?

- Mamochka’s (Mother’s) Apple Dessert.

- Sherried Chicken or Turkey – “This goes back to Russia. It is one of the dishes served frequently at the Easter festival. This is good with Brussel sprouts and orange salad”.

Genia was an accomplished seamstress and made a wedding gown for Liz Chatten. She was active in both a book club and a bridge club. The photo shows Genia (second left, top row) and Nonna (far right, top row) at a birthday party for a member of their ladies’ bridge club. My mother-in-law, Marie Roblin (second left, bottom row), always called the group “The girls”.

As she grew older, Genia became less able to manage for herself and moved to Halifax to live with her daughter Alice. She celebrated her 100th birthday in 2001, passed away in 2002 and is buried in Mount Hope Cemetery, Brighton.

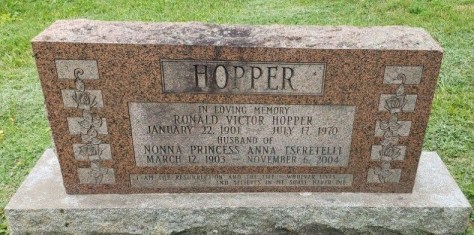

Ronald retired in 1966 at age 65 and, while working the farm, Ronald and Nonna became very active in Liberal politics and hosted many political events. They also added an addition to the farmhouse so that both families could live there. Things changed dramatically when Ronald died four years later after being cared for at home. Nonna threw herself into learning the apple business, managing the farm and taking driver’s lessons from neighbour Earle Chatten. She wrote letters to politicians and newspapers, lamenting the meagre share of the retail price of apples that is given to the grower, who had to take all the risks. The town population had almost doubled to 2,700.

Nonna was very outgoing and loved parties and interacting with everyone. She was always well-dressed and often sported a unique hat with her outfit. Both women chain-smoked, and Nonna was the athlete in the family – playing golf at Barcovan.

They did whatever they could to ease the burden on their mother in Russia, by sending money often and appealing, to no avail, to the authorities to contact their mother to allow her to immigrate. They never returned to Russia because they felt that their lives would be at risk.

The sisters seemed to love the town, and the town loved them back. They were active members of St Paul’s Anglican Church. Nonna volunteered to do anything at the local Community Care office that would help others and canvassed for the Canadian Cancer Society.

Nonna’s health began to fail, and she was admitted to Applefest Retirement Residence to receive daily care. In 2003, a gala celebration was held at the church for her 100th birthday. Nonna sat and visited with all of the many friends she had made over the years. She died in 2004 at the age of 101.

They were citizens of Russia, citizens of the world, citizens of Brighton and should be honorary citizens of Legacy Brighton. They would have been delighted to have been here: Genia with her painting and cooking and Nonna would have loved meeting at every lunch and dinner with three other “Dahlings”. They both rest in Brighton’s Mount Hope Cemetery – 4200 miles from their place of birth.

Lives well-lived

They were citizens of Russia, citizens of the world, citizens of Brighton and should be honorary citizens of Legacy Brighton. They would have been delighted to have been here: Genia with her painting and cooking and Nonna would have loved meeting at every lunch and dinner with three other “Dahlings”. They both rest in Brighton’s Mount Hope Cemetery – 4200 miles from their place of birth.

Lives well-lived

You must be logged in to post a comment.